Shotgun Pattern Testing

Another

test conducted by firearm examiners is known as Shotgun Pattern Testing.

This test involves shotguns and allows for a muzzle-to-target

distance to be determined.

Shotgun

pattern testing involves examining evidence for a pattern of holes

created by the pellets fired from a shotgun. The

"unknown" pattern is then compared to "test" patterns created

with the suspect shotgun fired at known distances. This will allow

for an approximate muzzle-to-target distance to be

determined.

Two overlapping shot patterns. A large

dispersed

pattern overlaps a small close-range shot pattern.

When a

shotgun is fired using a multiple pellet shotshell, the pellets exit the

barrel of the shotgun and begin to spread out into a pattern that

increases in diameter as the distance increases between the pellets and

the shotgun.

To better

understand the principles involved in shotgun pattern testing it's

important to first learn a little about shotguns and the shotshells they

fire.

Shotguns

are firearms typically fired from the shoulder that are designed to fire

shotshells containing anywhere from one large projectile to as many as

several hundred small pellets. Shotguns

aren't classified by caliber but come in different gauges.

The gauge of a shotgun is determined by the number of round lead

balls of bore diameter that it takes to equal one pound. Shotguns

can come in 10, 12, 16, 20, 28, and .410 gauge. The .410 is

actually an exception with .410 referring to the caliber of the

shotgun's bore. It would actually be about a 67 gauge in

"lead ball" terms.

Although

some newer shotgun barrels are produced with rifling, shotguns have

traditionally had smooth bored barrels. Except in some rare cases

the projectiles fired from them cannot be matched back to the shotgun.

Auto loading shotgun with conventional

barrel (top) and

an auto loading shotgun with a rifled "slug" barrel (bottom).

Shotguns

come in a number of different styles and actions. From auto

loading shotguns like those seen above to very "customized"

versions like the one below.

"Sawed-off" pump-action

shotgun.

Shotguns

are typically manufactured with what is called a choke in

their barrels. A choke is a constriction in the last couple of

inches in the barrel and can vary in the degree of constriction.

Common choke designations are "full", "modified",

and "improved cylinder." A barrel that has no choke is

referred to as a cylinder-bore barrel.

Barrel modified for use in a

"Turkey-Shoot" competition.

Extreme constriction or choke can be seen at the muzzle.

Shotguns can be manufactured with a permanent

fixed choke or can have the muzzle of the barrel machined in a

way to accept interchangeable or adjustable choke

tubes. Shotguns that have had their barrels sawed off have had

their choke removed. This creates a shotgun with a

cylinder-bore barrel.

The whole

point to this "choke thing" is that the choke plays an important role

in the rate at which the shot pellets spread as they travel away from

the shotgun. A full-choke barrel will tend to shoot smaller shot

patterns at a given distance than a barrel with a modified-choke.

Shotshells

are cartridges designed to be fired in shotguns and can contain a single

large projectile - a slug - or as many as several hundred small

spherical pellets called shot. Shot used in

shotshells has traditionally been made of lead but because

of it's toxicity, other materials are being used as a

substitute, with the most common alternative being steel.

The size of the shot can vary as can the total weight of the shot

loaded into a shotshell. Shot comes in two basic varieties, small

pellets commonly referred to as birdshot and larger

pellets called buckshot.

Components from a typical shotshell

containing

birdshot and a one-piece plastic wad.

Components from a typical shotshell

containing

buckshot and a fiber/plastic wad combination.

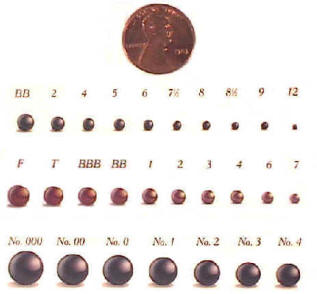

Lead

birdshot

comes in 12, 11, 9, 8 1/2, 8, 7 1/2, 6, 5, 4, 2, and BB sizes. As the

numbers get smaller the diameter of the shot gets larger. Buckshot on

the other had comes in 4, 3, 2, 1, 0, 00, and 000. Again, as the

number decreases the diameter increases. See the chart below.

Shot size table: lead shot (top), steel

shot

(middle) and buckshot (bottom).

As you can

see from the above chart, steel shot comes in slightly larger sizes than

lead shot. Steel doesn't have the density of lead and larger shot

is needed to achieve a range comparable to that of lead shot.

Shotshells

contain a variety of different wads - plastic, paper, or

fiber material designed to separate the shot from the gunpowder and/or

protect the shot as it is

pushed down the barrel - that are expelled from the

shotshell, along with the shot, when fired.

Various plastic and fiber shotshell

wads.

Shotshells

come in a variety of loads. The amount of gunpowder in a shotshell

can vary and the measurement is referred to by as the dram equivalent.

The dram equivalent is the amount of smokeless powder that produces a

velocity comparable to that of black powder.

All of these variables

are important in determining a given shot pattern distance.

When a shotgun is fired the shot and wadding

travel down the barrel and exit the muzzle in a concentrated

mass.

As a

result a contact entrance hole will produce a large hole with

significant damage to the margins of the hole, but can vary greatly

depending on the material being fired into. The same thing also applies to

gunshot residue deposits. Most contact entrance

holes will have a significant deposit of gunshot residues like the one

seen below, but this is not always the case. Some may display very

little visible gunshot residue.

Contact shotgun entrance hole.

A hole

like the one above will be processed chemically like that previously

described on the Distance Determination/Gunshot Residue pages.

At ranges

of around 5-10 feet* the shot and wadding mass will produce a single

large hole in a target. If the target happens to be a person, the

wadding material will be blown into the wound tract with the pellets.

Close-range shotshell pellet entrance

hole.

The close-range entrance (less than 5 feet*)hole

seen above is almost square, and is a common shape for this

range. You might notice a pinkish color (lead residue) to

the material around the hole.

At

distances greater than 5-10 feet* the shot mass starts to break up. Fliers

(individual

pellet holes) will start to appear around the edge of an entrance hole and the

wadding may or may not enter the victim.

Individual pellets starting to break

apart from the main mass of pellets.

As the

wadding slows down it will start to take a separate trajectory from that of the shot

and can actually leave abrasions or bruises to the area

around an entrance wound. Wadding will lose its energy and fall

harmlessly to the ground at distances of around 20 feet*.

As the

pellets get further and further away from the shotgun the pattern will

eventually become dispersed to the point that only individual pellet

holes are present in a target.

Witness panel fired into at a

distance of 28 feet.

Firearm examiners will try to reproduce the

pattern by firing into witness panels at known distances. Shot

patterns can be affected by the load, pellet size, wad type, and

choke of the shotgun. That is why it is essential that the

shotgun is recovered and the type of shotshells used is known.

Hopefully some shotshells will be recovered at the scene that

can later be used in firing the distance standards. Also,

patterns produced by a shotgun at any given distance can vary

slightly. Multiple tests patterns will be fired at known

distances and compared directly to the pattern in question.

Based on this comparison a minimum and maximum firing distance

can be determined.

Unlike the tests conducted on clothing for gunshot

residues, shotgun pattern testing is not limited to distances of

a few feet or less.

*All

distances are approximate values and can vary depending on the shotgun's

gauge/choke and ammunition used.

|